-

play_arrow

play_arrowClub Ready Radio Dance Freex Radio

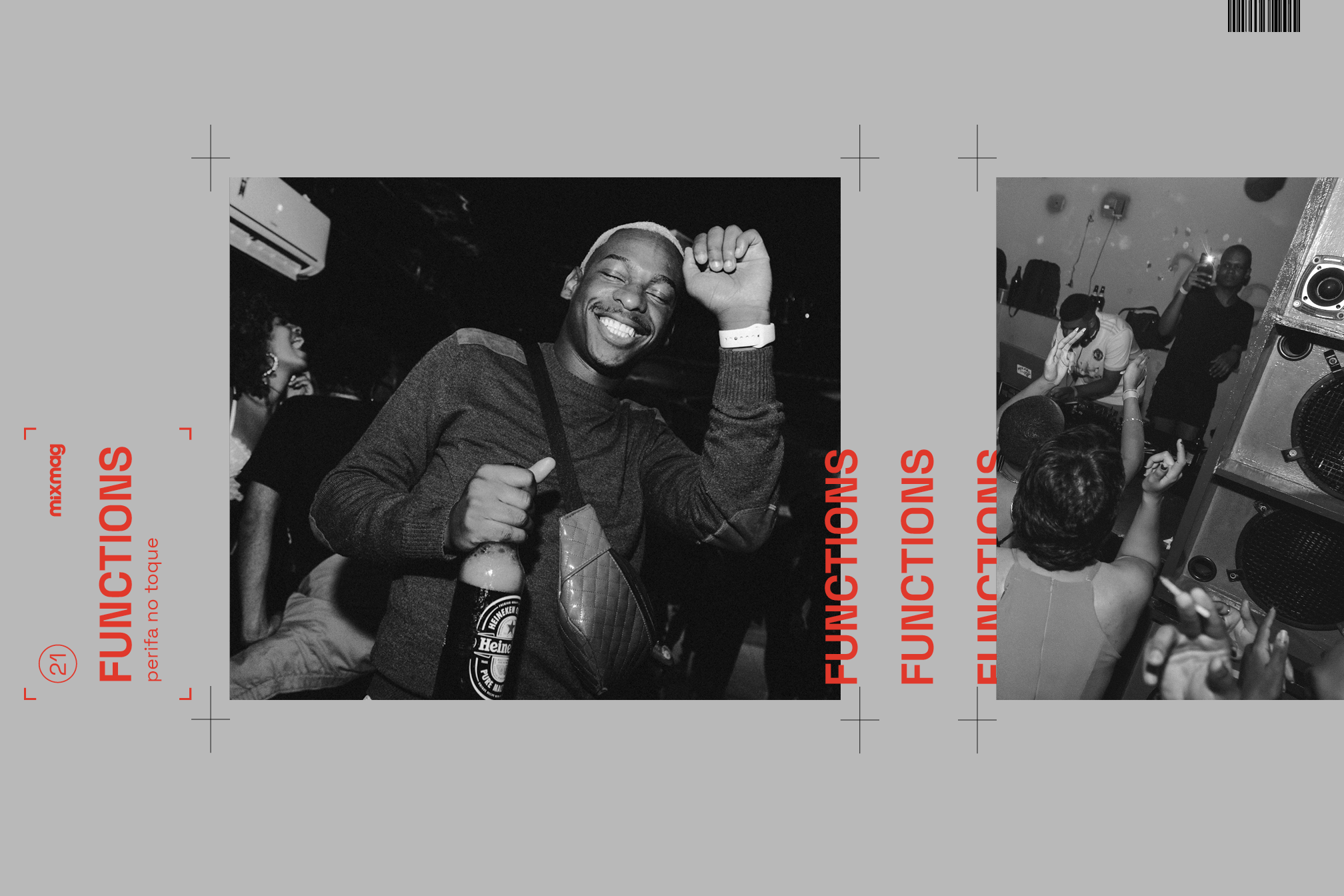

“The ends rule”: Perifa No Toque is a baile funk haven for people on the fringe of São Paulo

Features

FeaturesMixmag caught up with two of the key members of the party for people on the city’s peripheries, to chat about its rise from a tongue-in-cheek barbecue fundraiser to one of its most important proponents of an often demonised genre and culture

- Words: Isaac Muk | Photos: Perifa No Toque

- 21 April 2023

In a supercity like São Paulo, with a population of over 21 million in its greater metropolitan area – more than London and Paris combined – existing on the city’s margins takes on a whole different meaning. When it can take hours to travel in between the various districts, living on the city’s outskirts literally means the margins of society.

“Sāo Paulo is huge, the city is very big,” says Peroli, a co-founder Perifa No Toque. “We don’t have good [public transport] – it’s very far to go from South to East, to go to Central – it’s madness. A lot of people live [in the outskirts] and have to travel for one or two hours every day to go to work.”

Within Sao Paulo’s concrete ocean, the city has spawned a thriving, diverse, underground party scene over the past decade. Cashu and Laura Diaz’s Mamba Negra has gained international recognition for its queer-positive raves, while the same goes for BATEKOO and its focus on the city’s LGBTQ+ POC communities.

Over the past few years, Perifa No Toque has carved out its own distinct place within the city’s busy scene – a central party that caters for people on the fringes of society, both culturally and geographically. Featuring an ever-expanding crew, but united by their love of funk and outside-looking-in perspectives, it has grown from a consistently sold-out party to a wider online platform and community since first opening its doors in 2019.

“I’m from Capāo Redondo,” says Thalita, another Perifa No Toque crew member. “It’s an outer zone of Sāo Paulo, and it’s a huge neighbourhood. I’m from the periferia ghetto, and baile funk has always been close.”

Read this next: Seventh Heaven: Pervert gives space for Mexico’s hedonists to feel alive

Injecting the local underground sounds of baile funk with grime, dubstep and UK bass influences, the party has also become a unique place to find some of São Paulo’s most forward thinking, weighty music. But like how grime and drill were demonised in their infant days across the Atlantic in the UK, baile funk music and culture is often looked down upon in Brazil – as music from the ghetto, parties are often shut down and nightclubs often favour the more socially acceptable sounds of house and techno. Perifa No Toque aims to subvert this, highlighting the positivity of the music, community and life in the suburbs.

We caught up with Peroli and Thalita, two DJs and key members of the crew, to chat about the party, the “criminalisation” of baile funk in Brazil and the sounds of Sāo Paulo’s underground.

What were your first experiences of dance music and dance music culture?

Peroli: I’m from a city that isn’t quite inside the city of São Paulo, but inside the [greater metropolitan area] called Sāo Bernardo. So life was more chill and calm, the rhythm of life is very different. I started going out around 2000 when I was really young, like 13, 14, because my mum was a DJ, so I was really part of the hip hop culture from my early ages.

Thalita: Hip hop culture was so strong in Capão Redondo, and I started going to see MCs battle rap. I got involved with all the elements of hip hop culture, like graffiti, breakdance, and became really amazed by the world. I didn’t come from a family that listens to so much music in the house, so all of the music that I listen to today is from things that I learned with friends, places that I started to go to, and my own personal research. After I started discovering hip hop culture and how the streets constructed it, I started going out downtown.

Read this next: 10 crucial tracks telling the history of São Paulo’s baile funk scene, curated by Baile LDN

How did you guys all meet and then how did you come to start the party?

Peroli: The party started from this urge that we had, because at some point in Sāo Paulo we used to have a lot of street parties, block parties and underground parties [that played] bass music. But we didn’t have a lot of places to go to where we could listen to the music that we wanted to. Eduardo, the other partner started started the party and brand with another partner – not as a joke, but kind of as a joke. They had this free day at a venue, and their aim was not to make profit – any profit they’d make they would make a huge barbecue for their friends.

They had this mindset because baile funk isn’t accepted in some clubs, even nowadays. So they wanted to do something to celebrate the culture and create a safe space for everybody to go to. Because people have to travel so far, we wanted to occupy central spaces with baile funk, which is not something people accept. I met Eduardo and Vitor in 2016 at grime and dubstep events, and even people there said: “Ah funk, we don’t want to hear that here.” So there was always this prejudice, and we decided that we wanted to do something out of the curve, but at the same time bring the people who celebrate that with us and people who share the same music taste.

Can you tell me a bit more about the criminalisation of baile funk?

Peroli: Clubs weren’t allowed to have parties where baile funk is being played. The venues, managers, the police, the councils didn’t want them. We have block parties, like street parties on the periphery of Sāo Paulo, but they are shut down every day. We [also] have so many layers of baile funk, what you hear is just the surface – what the media deems acceptable, but we have a bunch of underground layers of baile funk that’s deeper than that.

Thalita: It’s so crazy, because when we talk about doing baile funk in the middle of a city like Sāo Paulo, it becomes a huge operation for the police and the City Office. And some of the venues that open their doors to parties try to break the experience that we try to provide.

Peroli: I think it’s similar to how drill is perceived – when people think of drill they think about gang violence and similar things to that – so some people think that the frequency of some type of genres of funk make people violent, make people want to have sex, make people want to use drugs. If they have baile funk in their mind, they think that people will be using poppers all the time, that they will carry guns around – this is something that is generalised in the country but every state has its own particularities.

And it’s grown into more than just a party right? Can you tell me a bit about that?

Peroli: After the first parties, it became big, so we started thinking about how we can personalise this? So Thalita came, Lucas, our art director came, and we have a bunch of other collaborators who create content for the website, so Perifa started becoming a creative hub, where people can develop their creative projects.

Read this next: The Importance of getting lit: Club Djembe supplies feel-good beats for dancers who love to get down

Can you tell me a bit about your music policy?

Peroli: We have a lot of DJs who play baile funk in the peripheral areas of Sāo Paulo, bringing [what they play] into the club. [We want] people to see that what they listen to on Spotify isn’t actually what the streets listen to. And we try to showcase the good side of what it actually is – we say it’s a safe space, no fighting, no guns, no drugs. And it’s important because for people who live in the peripheral areas, this is what they do! It’s important not to shame these events and the music.

Thalita: There are no other parties that do what we do, in terms of bringing artists into clubs and venues that are most for white people and people who have family in the music industry.

There seems to be a thriving scene in Sāo Paulo for radical parties promoting inclusivity, like BATEKOO and Mamba Negra – why is it so important to have parties like theirs and yours in the city?

Thalita: It’s really important. We did one or two editions with BATEKOO, which is a big party here and is on the global market. But BATEKOO is like our cousin, we do different things with different impacts – they are more focused on queer people and Black people. We are focused on queer people and Black people too, but our court is more with peripheral people, because there are a lot of white people in these spaces too – and we can’t exclude them.

What sort of things do you do to make Perifa No Toque as safe and inclusive as possible?

Peroli: We always try to have tickets as cheap as possible, so people can afford to come. We also try to find venues that welcome people from the peripheries as well. And the days and times as well, because a lot of people work on Saturdays, so if we do a party on a Friday, the crowd will be smaller. The aim is to always do it in the central areas, but last year we did a lot of events in some of the cultural spaces that we have in the [outskirts of] the city.

There’s this [annual] 24-hour event organised by the City Office, where they put stages all across the central areas of the city – through the night. We did that and it was the first baile funk stage ever, and we had no problems, no fights. It was really important for us because of the way baile funk is often related to bad things, and also when we do events like that we don’t need to charge, they’re free.

Thalita: We’ve done a lot of free events, and we also aren’t afraid of saying no to proposals if we think that they don’t match with the things that we believe in. We’re also not afraid to question security and staff if they are being too much and not treating us or the people who come to our parties, and stand up to them because it’s our responsibility – it’s kind of obvious but not everyone does that.

Can you tell me a bit about the particularities of São Paulo’s baile funk scene?

Thalita: When we talk about baile funk in Brazil, it’s not one massive generalised thing all across the country. We’ve got São Paulo funk, we’ve got Rio de Janeiro funk etc. And we’ve got our own aesthetic – we’ve got crochet hats that have become the symbol of baile funk. People learn the handwork and art while they are in prisons, so it’s all related – some clubs have rules saying that people can’t get in if they’re wearing these hats or football shirts. And this connects with the marginalisation of Sāo Paulo baile funk.

Peroli: Sometimes the security can be rough, but most of the time we need to work with the venue staff. But we always like to have some of us at the door, some of us in the DJ booth and some of us on the dancefloor, so we can all be aware of what’s going on and to solve any problems if we need to.

What’s your favourite party that you guys have ever done?

Thalita: I don’t know if I can choose just one, but our third anniversary party was the first event [we did] after the pandemic, so it was huge. It was in the club where we did the first one – it was sold out and a lot people tried to get in. There was a buzz on social media, people saying like: “Oh my god I travelled across the city and couldn’t get in.” It was a challenge but it was important for us to understand how big our party had become. There was a one-year lag in our parties, and it was a shock for us to understand, like: “Right, now it’s really serious.”

Peroli:That day there were people queueing from 9:PM – the party started at 11:PM!

Do you think you grew during the pandemic?

Peroli: Yeah, because people were missing us so much! It was funny because there was this pandemic period when people were always like: “Oh, I’m missing going out.” But every other week there was people like: “I miss going to Perifa. It’s warm outside, we should be going to Perifa.”

Thalita: And it wasn’t like we were just sitting down and waiting until we could do parties again. We had a lot of DJ sets that we put on YouTube, and we made some live streams. It wasn’t super [well] produced – it was kinda trash, but people liked it and engaged with us. And it was a good time to put forwards our social and educational projects to the public, such as things on our website and consulting for brands and companies in the context of culture.

Read this next: Brega funk is the music of Recife that’s taking over Brazil

And what does the name Perifa No Toque mean?

Peroli: It sort of translates to ‘the ends rule’. Basically what it is, all of the trends that happen in the country – musical trends, cultural trends, fashion trends – are ruled by people from the peripheries.

What’s next for Perifa No Toque?

Thalita: The million-dollar question. It’s kind of hard to answer right now, we are thinking a lot about our trajectory. We aren’t real good planners, we are just doing at the moment. Like Peroli said it all started for a barbecue, but looking forwards I think a big deal for us is to communicate all the other things that we do. Maybe increase these external projects, because let’s be real doing parties doesn’t make us any money, but we want to make a difference for people who have followed us throughout all this time.

For more info on Perifa No Toque follow them on Instagram.

Isaac Muk is Mixmag’s Digital Intern, follow him on Twitter

Written by: Tim Hopkins